Key Takeaways:

- Construction and demolition waste make up approximately 40% of the US waste stream

- Buildings account for 40% of the global use of raw materials –– many of which are non-renewable

- Reuse of building materials can drive a circular economy and reduce carbon emissions

- There are more resources than ever to recycle building materials and furnishings when undergoing a renovation

Construction and demolition waste accounts for upwards of 40% of the US waste stream. In 2018 alone, the US generated 600 million tons of construction and demolition debris. Of that, 90% was from demolition with the remaining 10% coming from construction.

This has become a major problem globally, particularly as the “take, make, waste” economy has prevailed. In fact, not only is construction and demolition a primary contributor to waste, it’s also one of the biggest users of the Earth’s raw materials.

Now there are efforts large and small in communities the world over to make construction more circular. And one way of doing that is to extend the life of construction materials by cycling rather than landfilling them –– an effort that will require the buy-in of everyone from home and building owners to architects to construction professionals and designers.

Shifting from demolishing to reusing

It’s become second nature to start with demolition when undergoing a renovation project. Get the old stuff out as quickly as possible to make way for the new. But this approach has created a heaping waste and emissions problem, not to mention depleting the Earth of non-renewable resources.

According to the US Green Building Council (USGBC), buildings account for 40% of the global use of raw materials, which equates to roughly 3 billion tons annually. Despite the amount of raw materials consumed every year, only approximately one-third of all construction and demolition (C&D) waste is recovered and reused.

Many of these materials could find renewed life in the form of flooring, road-building materials, gravel and erosion control, etc. Fixtures and other furnishings in commercial and residential spaces can also often be preserved and find life in a new space or reimagined for something completely different.

In fact, to shift this problem, reuse has become a priority in a number of countries. And this includes not just the reuse of materials, but the reuse of the current building stock––extending the lifespan of buildings and infrastructure through renovation.

Reusing to reduce embodied carbon and energy

As Carl Elefante, the former president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), once said, “The greenest building is…one that is already built.” Similarly, former eBay CEO, John Donahoe, maintained that the greenest product is the one that already exists.

Though it may seem counterintuitive, especially when considering less energy-efficient older buildings, building replacement is highly energy- and carbon-intensive. Like new products, new buildings require drawing on new natural resources to produce.

Building products––including structural elements to finishes, and everything in between––are among the biggest contributors to carbon emissions. This is partly because producing them can be highly carbon-intensive. Materials like concrete, steel and aluminum, which are the most commonly used in structural elements, produce approximately 20% of emissions.

From the extraction of the raw materials to the transportation to the process of converting them into an end product, each step requires energy and produces carbon. Often, embodied energy and embodied carbon will be used as measures to understand the environmental impact of a product, material or building.

Embodied energy refers to the amount of energy used to produce a building, product or material. This includes all phases of its lifecycle from extraction to fabrication to assembly and use, and finally, deconstruction and disposal. Each step requires energy in some form or another. Embodied carbon, on the other hand, refers to the greenhouse gas emissions that result from the manufacturing, transport, installation, maintenance and demolition and disposal of a building, product or material.

In most cases, the majority of total embodied carbon is released upfront in the extraction and production phases. Thus, the longer something stays in use––provided it meets health and safety requirements––the more it will reduce the need for new and reduce the overall impact of that product, material or building over its lifetime.

Rethinking the old system

Even though reuse has become a more favorable option for many architects, designers and owners, there are several big challenges that stand in the way of it becoming mainstream, including:

- Matching the supply to the demand

- Educating owners about what can be reused and recycled

- Connecting the resources

- Changing old habits, perceptions and misconceptions

“One of the biggest challenges is we’re working against a system that’s been completely designed to make it easy for people to throw things away,” said Mike Gable, president of Build Reuse and executive director of Construction Junction, a nonprofit that supplies surplus construction materials. “It’s cheap to landfill materials so there’s not a really strong economic incentive to look for opportunities to not throw things away. The whole system is very much geared toward making it convenient to throw things away.”

Aside from the convenience factor, most simply don’t realize how much potential is within their four walls.

“When people want us to come look at a building, often they’ll say ‘There’s nothing in this building you guys will be interested in,’” Gable said. “But there are very few jobs that we go into where we don’t find anything. And that surprises a lot of people.”

Karen Jayne, CEO of Stardust, a nonprofit organization that provides deconstruction services and operates reuse retail centers for gently used and surplus building materials, echoed that sentiment.

“In general, we are a disposable society,” she said. “Once we decide we do not want it anymore we throw it away. This is true in all facets of life including when people are remodeling kitchens, bathrooms and whole homes. Over 75% of the materials in those spaces are reusable.”

The other challenge that comes for those who do want to reuse or recycle their unwanted building materials, fixtures or appliances is finding deconstruction resources as well as the places that will intake those items. In communities without resources like Stardust or Construction Junction, where do you go? Or what about the items that are harder to recycle such as PVC or old paint cans?

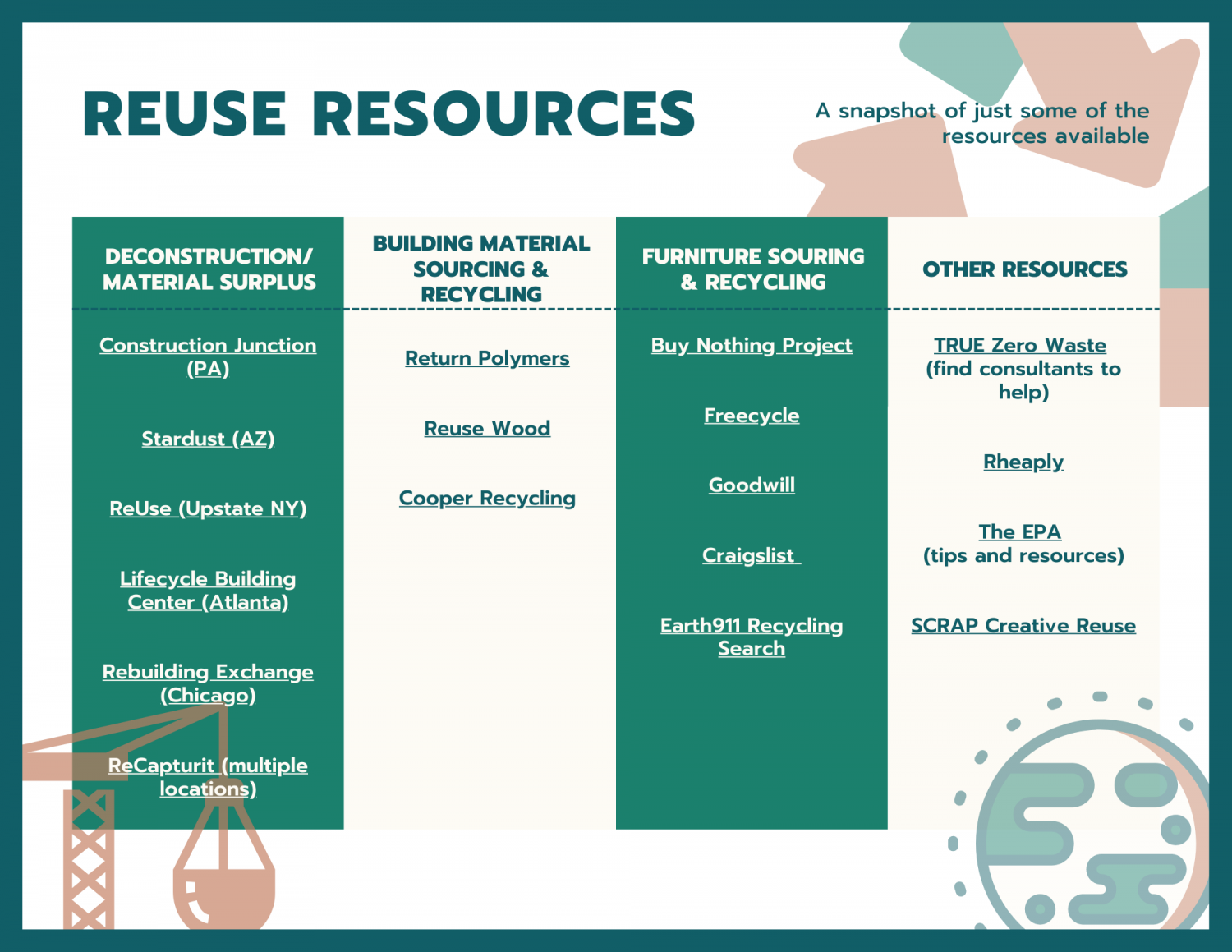

Luckily, there are more resources springing up around the world. Here are just some from throughout the US:

With most renovation or tear-down projects, a good place to start is usually with a local reuse center. If they can’t take certain materials, they may be able to refer a resource that will. And now there are more and more innovative companies around the world that have figured out how to take demolition waste, industrial waste and even by-products from production and recycling processes to create things like brick, tile, acoustical ceiling solutions, and more.

“In the building material reuse world, there’s kind of two streams of materials,” Gable said. “There are building material components––cabinets, sinks, light fixtures, appliances, doors, windows, etc. Then there are the more aggregate materials like metals, concrete, steel, glass, and things that are more readily identified in the construction waste stream as things that can be recycled.”

With most materials able to be reused or recycled, circularity has another benefit aside from creating a healthier environment, it also supports economic vitality, particularly in local economies.

Reusing to fuel a circular economy

The take, make, waste model is very linear. Once a product, material or building is thrown out or demolished, it’s taken out of the stream and replaced with a new one. On the surface, this model seemingly contributes to economies of scale. But could a circular economy rooted in reuse stimulate deeper economic vitality?

The concept of the circular economy is about keeping things in use for as long as possible. It’s reuse versus consuming and throwing away. And a reuse economy is not only labor intensive––employing more individuals––it also produces a number of downstream opportunities for numerous stakeholders. For instance, a demolition project might only require two people using some heavy-duty equipment one to two days to complete, where deconstruction will employ six or more people over the course of a week to 10 days. And the material extracted has potential to generate revenue again.

“If you’re demolishing a building that material is taken to a landfill and most of it gets put in a big hole,” Gable said. “Now the economic potential of that is done.”

Alternatively, when buildings are deconstructed, more people are employed throughout the entire process––deconstruction, transportation of materials, sorting, preparing for resale, and selling the materials. Those materials or goods are then bought and repurposed for use or, in some cases, refurbished and resold for a profit.

“The economic impact is exponentially higher than an economy based on take, make, waste,” Gable said.

Jayne also added, that the benefits of deconstruction and reuse are numerous, and can:

- help offset costs associated with remodeling by providing a tax deduction for the materials removed;

- conserve landfill space (On average, deconstructing one kitchen diverts 2,400 lbs. of usable materials from the landfill);

- preserve historically significant materials;

- reduces the environmental impact of producing new materials;

- provides affordable, quality materials to the community;

- and reduce trash disposal costs.

“Once people recognize the value in preserving the materials for reuse and how that action can benefit the community and environment, we will have made a giant step forward,” Jayne said. “That includes homeowners, general contractors, designers, architects––all of us.”